By Cathy Yarbrough

When Alice Accorsi, PhD, first encountered the freshwater snail Pomacea canaliculata, it was as an invasive pest of crops and the intermediate host of a parasitic roundworm that can cause human encephalitis.

Accorsi, then a graduate student at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Modena, Italy, was searching for vulnerabilities in the snail’s immune system that could be targeted to eradicate the pest.

Today, as a postdoctoral researcher at the Stowers Institute, Accorsi is one of a few scientists worldwide who is studying P. canaliculata not as a pest, but as a new laboratory model for research on the molecular and cellular processes responsible for the regeneration of complex eyes.

Like humans, this snail has camera-type eyes that use a single lens to focus images onto the retina. Unlike humans, however, the adult snail can completely regenerate its eyes after they have been damaged or experimentally removed.

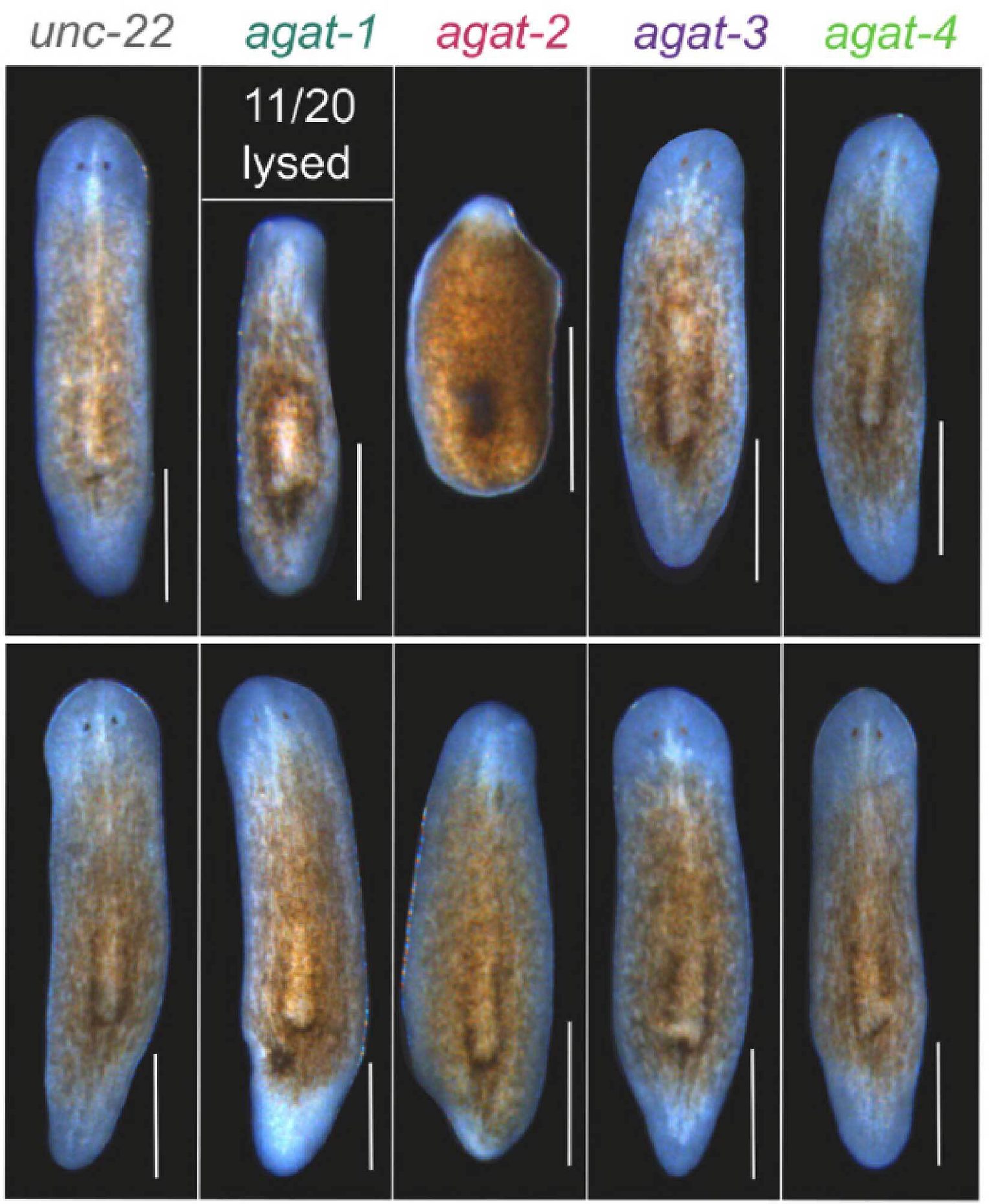

Accorsi’s scientific interest in regeneration began at the Marine Biological Laboratory’s 2013 summer embryology course in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. There, she met Stowers Investigator and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Investigator Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, PhD. A director of the annual course since 2011, Sánchez Alvarado is one of the pioneers in the science of regeneration. A major focus of research in his laboratory has been investigating the role of stem cells in regeneration using the planarian flatworm as a model organism.

Before returning to Italy, Accorsi talked with Sánchez Alvarado about her newfound interest in regeneration and her then current research on the P. canaliculata immune system. “Alejandro’s lecture inspired me and made me curious about the potential ability of P. canaliculata to regenerate, so when I returned to the lab in Modena, I was able to witness firsthand the snails regenerating some severed body parts over a one-month period,” she said. Sánchez Alvarado also encouraged her interest in regeneration, and the following year, in 2014, Accorsi spent three months as a researcher in his lab at the Institute.

“The experience helped me define my interests and the scientific questions I would like to answer as a postdoc,” Accorsi says. “It was as if I had discovered a new world!”

A year later, Accorsi returned to the Sánchez Alvarado Lab to conduct her postdoctoral studies on regeneration in P. canaliculata. Accorsi hopes to uncover the biological mechanisms that regulate the snail’s embryonic development of eyes and determine whether these mechanisms are similar to those that underlie regeneration in the adult animals. She also plans to determine how a complex organ, such as a cameratype eye, can be rebuilt de novo in the adults and how the regenerated eye cells communicate and connect to the preexisting cells in the snail’s nervous system. This research has the potential to lay the groundwork for the discovery of new mechanisms or molecules that might also have an impact on human health, Accorsi says.

In addition to conducting research, Accorsi has been busy with a novel educational project called The Planarian Educational Resource, Where Cutting Class Is Required. In collaboration with Sánchez Alvarado and other Stowers and HHMI researchers, Accorsi created the website and published a companion article, “Hands-on classroom activities for exploring regeneration and stem cell biology with planarians,” in the March 2017 issue of The American Biology Teacher. Accorsi hopes that the educational activities described on the website will encourage students’ interest in and enthusiasm for science.

Accorsi, who enjoys the music scene and the diverse cuisines of Kansas City, says that she “can’t think of a better place to conduct science than the Stowers Institute. We’re free to think big, and we do!”