Graduate students are budding scientists in training acquiring the skills to become independent thinkers and successful researchers. But they are also an integral part of the hands-on workforce, bringing enthusiasm, talent, and fresh perspective to the bench.

When Guangbo Chen talks about his research, eyes sparkle, hands fly, and the unexpected growth patterns of his research subjects—millions and millions of yeast cells—quickly turn into "a situation." In vivid detail, the graduate student training with Stowers Investigator Rong Li, PhD, describes visual observations that made him stop and think. In fact, it was a puzzling detail in the appearance of yeast cells he was growing in the lab that directly led him to the last piece of evidence for the Nature paper he just published.

Chen trained his visual sense early on. While growing up in China, he took regular art classes and was thrilled when one of his paintings was chosen to be included in a group exhibition in Japan. But it was his mother, a practicing internist who regularly brought her young son with her to the clinic, who drove home the importance of careful observations. "She was very good at looking at patients and data to figure out what was going on inside them," says Chen.

Chen's father, an engineering professor whose life was derailed by the Cultural Revolution when he was banished to the countryside for more than a decade, emphasized the importance of hard facts and actions versus ideology. "A lot of dinner table conversations focused on the value of doing science versus talking ideology," remembers Chen, which reinforced his decision to pursue a career in research. "Science is the most powerful way to change the world."

After graduating with a biology major from Fudan University in Shanghai, Chen enrolled in the Interdisciplinary Graduate Program at the University of Kansas Medical Center in 2007. But before traveling to the United States, he indulged his adventurous streak and embarked on a solitary bike ride through Shangri-La, a primarily Tibetan county in southwest China that was renamed in 2001 in honor of the fictional land of Shangri-La in the 1933 James Hilton novel Lost Horizon.

"For me, long distance bike rides are a great way to explore the world," says Chen. "It gives you time to take in the vistas, to see the mountains, the rivers and the people." These days, he's no longer satisfied with looking at mountains. Instead, he prefers to summit them. Two years ago, he climbed to the top of Handies Peak, an awe-inspiring fourteener in the Rocky Mountains, where he proposed marriage to his girlfriend.

The same intrepid attitude serves Chen well in the lab, where he isn't afraid of asking the big questions. "When I joined Rong's lab, I wanted to study how whole genomes respond to their environment," he says.

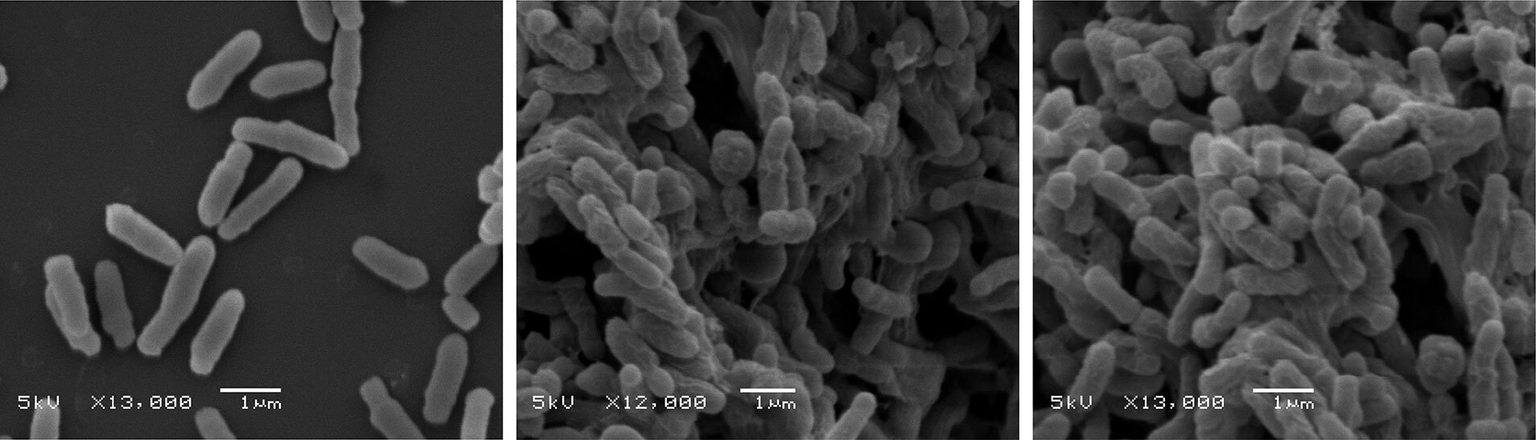

After three years of chipping away at the project, Chen's keen eye sealed the deal. When he grew some of his stress-adapted yeast cells under favorable conditions, he noticed their irregular surface. Baffled by what he saw, he launched a large-scale investigation assisted by the Stowers' famously supportive core facilities and research advisors.

"The cooperation not only improved the efficiency by combining different expertise," says Chen, "but was also an important learning process for me. When Chris Seidel helped us analyze the microarray data, I began to appreciate the power of computation in biology, and decided to take his course on genomics."

Before long, Chen was able to show that under stressful conditions yeast cells' genomes become unstable, readily acquiring or losing whole chromosomes to enable rapid adaption. "From an evolutionary standpoint, it is a very interesting finding," explains Chen. "It shows how stress it self can help cells adapt to stress by inducing chromosomal instability. Meanwhile, it may also help us to understand the root of genomic instability in other circumstances, such as cancer."

After his successful scientific premiere, the scientist-in-the-making is ready for more. "I really enjoy the investigative process," says Chen. “The high stake of resolving 'why' in biomedical research makes it an exhilarating adventure. I love adventure.”