KANSAS CITY, MO—Successful gene expression requires the concerted action of a host of regulatory factors. Long overshadowed by bonafide transcription factors, coactivators—the hanger-ons that facilitate transcription by docking onto transcription factors or modifying chromatin—have recently come to the fore.

In their latest study, published in the July 15, 2011, issue of Genes & Development, researchers at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research discovered that the highly conserved coactivator SAGA, best characterized for lending a helping hand during the early steps of transcriptional initiation in yeast, plays an important role in tissue-specific gene expression in fruit flies.

"It came as a real surprise," says Jerry Workman, Ph.D., the Stowers investigator who led the study. "Based on what we knew from yeast and the fact that SAGA is found in every fruit fly cell, we predicted that it would be play a more general role. "

Discovered in Workman's lab in the 1990s, the multi-functional SAGA, short for Spt-Ada-Gcn5-Acetyl transferase, regulates numerous cellular processes through coordination of multiple post-translational histone modifications. For example, it attaches acetyl tags to nucleosomes, the histone spools that keep DNA neatly organized, displacing them from active promoter areas and allowing the transcription machinery to move in instead. It also removes so called ubiquitin moieties from histone H2B assisting with the transition from the initiation stages to the elongation phase.

"In yeast, SAGA is thought to control transcription of approximately 10 percent of genes, most of which are involved in responses to external stresses," says Workman. "It is also associated with human oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes." Aside from its potential involvement in the pathogenesis of cancer, SAGA takes on an important role during the development of multicellular organisms in general.

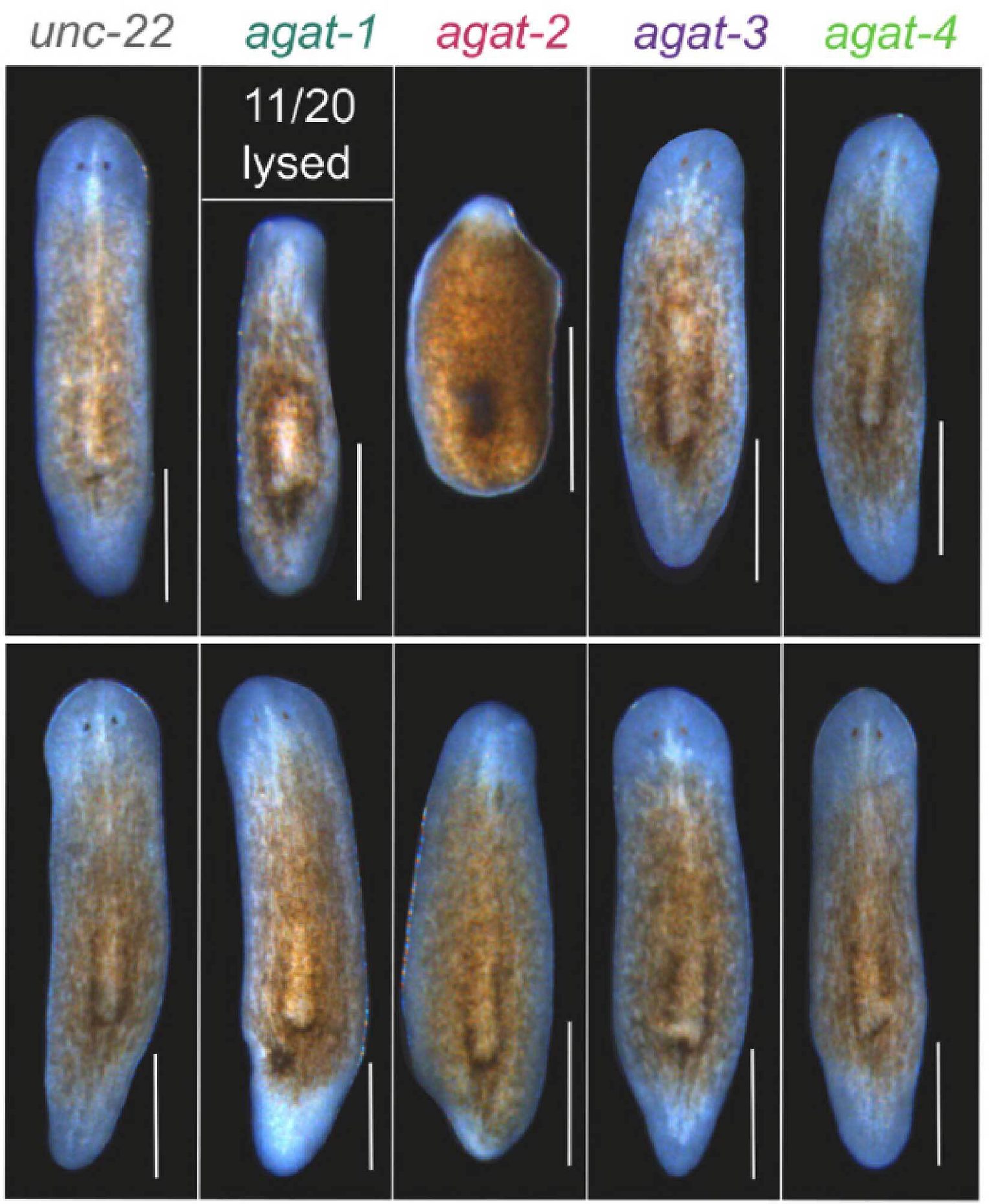

"A lot is known about how SAGA regulates genes expression in single-celled yeast but we wondered whether SAGA would have different gene targets in different cells, and if so—how would it be targeted to those different genes?" says postdoctoral researcher and first author Vikki M. Weake, Ph.D. To learn more about SAGA's involvement in developmental gene expression she decided to study the composition and localization of the SAGA complex in muscle and neuronal cells of late stage embryos of the fruit flyDrosophila.

Using a Chip-seq approach to determine SAGA's genome-wide distribution, Weake found that SAGA was associated with considerably more transcription factors in muscle compared to neurons. "The composition of the 20-subunit SAGA complex did not change in the two tissues we examined, even so SAGA was targeted to different genes in each cell type," say Weake. Which to her suggested that SAGA is targeted to different genes by specific interactions with transcription factors in muscle and neurons, rather than by differences in the composition of the complex itself.

When she took a closer look, she found SAGA predominantly in close proximity of RNA Polymerase II not only at promoters, the assembly site of the transcription initiation complex, but also within transcribed sequences. "SAGA had previously been observed on the coding regions of some inducible genes in yeast but our findings suggest that SAGA plays a general role in some aspect of transcription elongation at most genes in flies," she says.

In an unexpected twist, Weake detected SAGA together with polymerase at the promoters of genes that appear not to be transcribed and that therefore may contain a paused, or stalled polymerase. Paused RNA polymerase II, preloaded at the transcription start site and ready to go at a moment's notice, is often found on developmentally regulated genes.

"Pausing is not as prevalent in yeast as it is in metazoans," explains Workman. "It allows genes to be synchronously and uniformly induced. The presence of SAGA with polymerase that has initiated transcription but is paused prior to elongation suggests a prominent function for SAGA in orchestrating tissue-specific gene expression."

"It has only recently become clear in the scientific community that the release of paused polymerase II is commonly regulated and the mechanisms are still being identified," says Stowers assistant investigator Julia Zeitlinger, Ph.D., who was the first to discover stalled polymerase on developmentally regulated genes. "The study led by Vikki Weake suggests that SAGA could play a role in this, which is very exciting."

Researchers who also contributed to the work include Jamie O. Dyer, Christopher Seidel, Andrew Box, Selene K. Swanson, Allison Peak, Laurence Florens, Michael P. Washburn and Susan M. Abmayr.

The study was supported by the NIGMS and funding from the Stowers Institute for Medical Research.

About the Stowers Institute for Medical Research

The Stowers Institute for Medical Research is a non-profit, basic biomedical research organization dedicated to improving human health by studying the fundamental processes of life. Jim Stowers, founder of American Century Investments, and his wife Virginia opened the Institute in 2000. Since then, the Institute has spent over a half billion dollars in pursuit of its mission.

Currently the Institute is home to nearly 500 researchers and support personnel; over 20 independent research programs; and more than a dozen technology development and core facilities. Learn more about the Institute at http://www.stowers.org.