In The News

01 January 2026

Your Cells Are Always Building A Whole New You

From Science Friday, President and CSO Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado talks about the science of regeneration and the biology lessons we can carry into the new year.

Read Article

By Marla Broadfoot

On March 7, 2020, Stowers Investigator Jennifer Gerton, PhD, took her family to see a major league soccer game at Children’s Mercy Field. The air was electric, but as Gerton scanned the full-capacity crowd—18,467 smiling faces—she felt a growing sense of apprehension.

Every day, she had been following the numbers as more people in the US and around the world were infected with SARS-CoV-2. That day 118 new cases of COVID-19 had been reported in the US, bringing the total number of cases stateside to 400. As part of the then newly commissioned Stowers COVID-19 Task Force, Gerton was immersed in discussions about the Institute’s response to the unfolding crisis. That night, though, she was trying to cling to some remaining sense of normalcy.

Jennifer Gerton

“I remember telling my family to look around, to enjoy the game because it is going to be your last one for a long time,” says Gerton. “They called me crazy and said you’re just thinking about it too much.” It didn’t take long for her to be proven right. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected everyone, forcing people to adapt in ways they never envisioned. At the Stowers Institute, a combination of foresight, ingenuity, and determination averted some of its most distressing impacts. For example, not a single outbreak of COVID-19 occurred on campus. There were zero losses of research organisms due to the pandemic. And scientists were safely back at the bench months earlier than their peers. As we head into the end of another calendar year of the pandemic, members across the Institute are looking back at how they managed the worst public health crisis in a century, and what lessons they will take into the future.

Putting a plan in place

In January 2020, the Institute’s chief operating officer, Brent Kreider, PhD, noticed reports of a mysterious coronavirus-related pneumonia in Wuhan, China. At the time, his office was next to the office of David Chao, PhD, then president and CEO of the Institute. Their conversations centered on one topic as they watched SARS-CoV-2 spread throughout Asia and Europe and arrive in the US. In February, after the US declared a public health emergency, Kreider and Chao prepared for the worst—largely shutting down Stowers.

“We thought, how could we pull this off?” recalls Kreider. “There is so much interconnectivity across the Institute. Every single lab works with multiple technology centers every single day; if those shut down, the labs shut down, and the science shuts down. And we have thousands of research organisms on-site; we can’t just shut them down.”

Together they created a COVID-19 Task Force made up of administrative and operational members and scientists to advise them on how to shift operations and keep the Institute and its people safe. They set up a variety of different conditions for members and for research, such as “research with mitigation measures” and “research with limited people on-site.” They warned scientists to shorten the length of their experiments so they could end them with only a few days’ notice. And they grouped the lab technicians into pods to limit any potential COVID-19 transmission and reduce the number of people who might have to isolate or quarantine.

When Kansas City’s stay-at-home order was issued on March 21, 2020, the Task Force had established a detailed plan for an orderly shutdown just the week before. Almost everyone was sent home to work remotely, except for a skeleton crew. “It was ironic because one of my staff called the next day and said, how did you guys know we would need to shut down, and when?” says Kreider. “We really had no idea what day we’d need to transition to remote work—but had been planning for it all first quarter 2020.”

With the Institute in a reduced operating mode, unrest within the financial markets, and COVID-19 uncertainty all around us, the Institute also created the Strategic Management Committee. Composed of members representing all functions across the Institute, this group met—and continues to meet—daily to discuss both internal and external developments that could impact the Institute or its members.

Developing a test

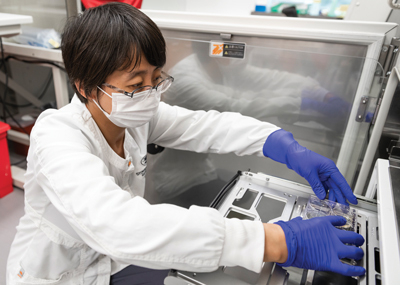

Many Institute leaders believed any hopes of returning to campus safely hinged on widespread SARS-CoV-2 testing to quickly identify positive cases and prevent larger outbreaks. But the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) had created testing kits that were contaminated. Many labs across the country began devising their own, homegrown coronavirus tests, and Gerton and other members of the COVID-19 Task Force suggested that the Institute do the same. On April 1, 2020, Gerton, Kreider, and Chao met via Zoom with one of Gerton’s longtime collaborators who had set up a viral testing program at the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub in California. Even though Gerton had studied virology as an undergrad and has a PhD in microbiology, she had a lot to learn about diagnostic testing, new technologies, and FDA guidelines. “It was a landslide of work from that point on—I was living and breathing and sleeping this stuff,” she says.

To get Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) from the FDA, the team had to run their test on paired sets of saliva and nasal swabs, thirty positive for SARS-CoV-2 and thirty negative. Gerton says it was easy to find negative clinical samples but collecting positive ones “proved to be a bridge too far.” The team was ten samples away when the FDA announced they were no longer granting EUAs for viral testing. In the end, the scientists gave all their data and protocols to MRIGlobal, a neighboring translational and scientific research organization and a certified clinical testing laboratory, to run the viral testing program. But because the Institute’s team had designed the test to be fully automated, they also had to pass along their giant sample-testing robot.

After MRIGlobal looked at the specs for the robot, they told Gerton it wouldn’t fit in the elevator. “I thought, we’re dead in the water because you could not for love or money order any of the automation equipment needed to run the test.” She asked about the size of the windows, envisioning a pulley system like one used to hoist a piano into a walk-up apartment. There were no windows in the lab. The team had already packed the robot onto the truck, and Gerton didn’t have the heart to tell them to bring it back in. So, she let them drive off. And somehow it fit.

Data driven

When MRIGlobal ran the new test, they showed it could detect as few as six copies of SARS-CoV-2 per milliliter of saliva—on par with the best tests available on the market. Stowers Institute Co-Director of Microscopy, Imaging, and Big Data Jay Unruh, PhD, who had helped manage many of the logistical challenges associated with the task, estimated that the Institute could prevent an internal outbreak if they identified 90% of positive cases and tested twice a week. The Institute’s test sensitivity ended up being 98%, allowing them to test just once a week. But Unruh and others were not completely satisfied. In addition to identifying people with an active viral infection, they were also interested in investigating who had COVID-19 in the past and now had antibodies against the virus.

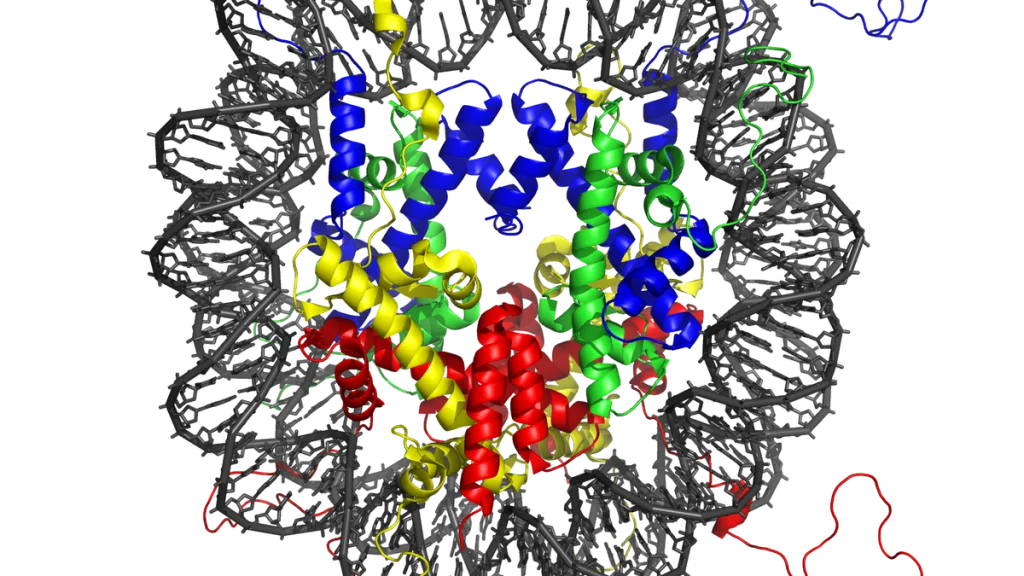

Former Investigators Joan and Ron Conaway’s lab and the Institute’s Cytometry Facility had already purified a large amount of synthetic spike protein, which adorns the surface of the coronavirus like a crown. The Stowers Institute Screening Facility and the Conaway Lab then developed a test that could detect antibodies to the spike, indicating a previous infection. Eventually, they had a test they could use to track antibody levels in 200 members and family members. “The results were crystal clear: anyone with strong COVID-19 antibodies had a positive viral test,” says Unruh. When they did antibody testing on over 100 volunteers who had not had a positive viral test, not a single one had a strong antibody signal. “We knew then that our population was still naïve, or largely unexposed.” At the time, only the small handful of people who had tested positive for the virus actually had antibodies.

Later, after members had been vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, the researchers started used the antibody test to monitor how well the vaccines were working. Their preliminary results indicated that all three vaccines—those from Moderna, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson—elicited a clear antibody response. “But the biggest surprise was how low the J&J antibody response was,” says Unruh. That response, on average, was less than the other vaccines and that of people who had not been vaccinated at all but had recovered from COVID-19. Unruh and the team published the method and results in a Bio-protocol paper.

KEEPING COUNT

22,464

COVID-19 saliva tests administered

603

COVID-19 vaccines administered at the Institute

263

Antibody study participants

1,465

Blood samples provided by members enrolled in antibody study

95

Members assisted with Institute COVID response

Into the fire

Laura Remy had just finished her PhD in nursing from the University of Missouri-Columbia in the spring of 2020 when she heard that Stowers was looking for a nurse with infectious disease experience to help guide its infection control policy. Remy, who had worked on infectious disease prevention campaigns in Africa, China, and India, interviewed and was hired on the spot. “Once I learned that Virginia Stowers had been a nurse, but that the Institute had never hired a nurse, I was in,” she recalls.

Shortly after joining Stowers, Remy was given less than 48 hours to set up drive-through testing so that Institute scientists and other members could return. “It didn’t seem doable, but we pulled it off,” she says. “We managed to test 500 people a week with very little waiting time.” Remy facilitated more than 22,277 viral tests and more than 1,094 antibody tests overall. While the testing program had been an administrative success, it also took an emotional toll when she had to tell members they had COVID-19. “It’s never gotten easier,” she says. Like others in the health care profession, Remy found herself fielding not just concerns about health but also frustrations over policies related to testing, mask mandates, and vaccines.

At one point, Remy hosted an Institute-wide webinar on compassion fatigue, encouraging people to care for each other and take care of themselves. When not wearing scrubs, Remy was often seen in a T-shirt emblazoned with Be Kind or We’re all in this together.

Caring for colleagues

There is so much interconnectivity across the Institute. Every single lab works with multiple technology centers every single day; if those shut down, the labs shut down, and the science shuts down. And we have thousands of research organisms on-site; we can’t just shut them down.

– Brent Kreider, PhD

“Even before the pandemic, mental health was a huge priority for the Institute,” says Jennifer Herbers, human resources manager at the Institute. “When we sent everyone home except for operationally essential personnel, we started recognizing that it was truly isolating. We were putting the testing in place to protect our members’ physical safety, so what could we do to support physical and mental wellness to combat the isolation?”

The Institute already had two popular wellness initiatives, InBalance and Stowers Connection, and could shift the programming to a virtual format. Through InBalance, the Institute created a two-part webinar with a parenting expert to help members working from home with children. Through Stowers Connection, the wellness team held a webinar on mindfully managing stress. They also offered several Mental Health First Aid courses, which taught members how to help coworkers struggling with a mental health issue. Other programs tackled different aspects of wellness. A work-from-home session covered the basics of ergonomics and technology. The fitness center offered virtual exercise classes and yoga recordings. And a new segment called Kitchen-to-Kitchen live-streamed café chefs as they made nutritious meals while Stowers members followed along at home. “What we’ve learned throughout this time is that mental health, and overall well-being, is so important,” says Herbers. “I think there’s a lot to learn, and even more we can do to support our members once we get back to whatever that new normal looks like.”

Redefining normal

Recognizing that many are still grappling with a world changed by COVID-19, the Graduate School of the Stowers Institute has worked over the last year to expand its mental health offerings. “Graduate students in general have higher levels of anxiety, and that only gets worse in the context of the pandemic,” says Jinelle Wint, PhD, the assistant dean of academic affairs. Through various mental health partnerships, the Graduate School and the Institute offer counseling resources to those who need them. But Wint wanted to do more, so she facilitated efforts to provide in-person therapy to the Institute’s predoctoral researchers through the Counseling Center at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and provided connections to other mental health resources in the community.

As the Institute headed into the fall, all were eager to make up for lost time. In conversations with other research institutes, Kreider has realized that the Institute, in many ways, fared much better than its peers. “In many ways we feel we were way ahead,” he notes. “We had all our services up and running when researchers elsewhere weren’t even allowed back on their campuses.”

“Since the beginning of the pandemic, we have closely followed CDC and local governmental guidelines to inform our decisions,” says Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, PhD, executive director and chief scientific officer of the Institute. “As the pandemic has shifted with the multiple variants, we do our very best to provide our members with a safe environment in which to do our very important work.”

Gerton and others on the COVID-19 Task Force—which still meets—are focused on keeping the science going, even amidst the emergence of new coronavirus variants like Delta. That means employing evidence-based policies, such as maintaining widespread COVID-19 testing, embracing a hybrid model to reduce the number of people on campus, putting masking in place when community transmission is high, and perhaps the biggest one of all: vaccines.

Despite the difficulties presented by the pandemic, there is a silver lining—scientists around the world were inspired by the pandemic to work together in unprecedented ways. At one count over ninety-three Institute members assisted with testing efforts. The Institute pivoted from its typical activities to create two high-quality and high-throughput COVID-19 tests that helped both the Institute and the community respond to the virus. The very fact that three safe and effective vaccines are widely available in our community a year and a half after the start of the pandemic is a testament to the resilience and innovation of science.

In The News

01 January 2026

From Science Friday, President and CSO Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado talks about the science of regeneration and the biology lessons we can carry into the new year.

Read Article

In The News

26 December 2025

From The Hindu, new research has found that the way the genome is organised can arise from chromatin’s own physics, without needing extra instructions

Read Article

In The News

22 December 2025

From Ophthalmology Breaking News, Stowers scientists study eye regeneration in apple snails

Read Article