In The News

07 January 2026

Investigator Kamena Kostova, named ‘Cell Scientist to Watch’

From the Journal of Cell Science, Investigator Kamena Kostova named a 'Cell Scientist to Watch'

Read Article

News

Stowers scientist discovers insights into how plants “talk” to bacteria in soil, possibly informing future antimicrobial therapies

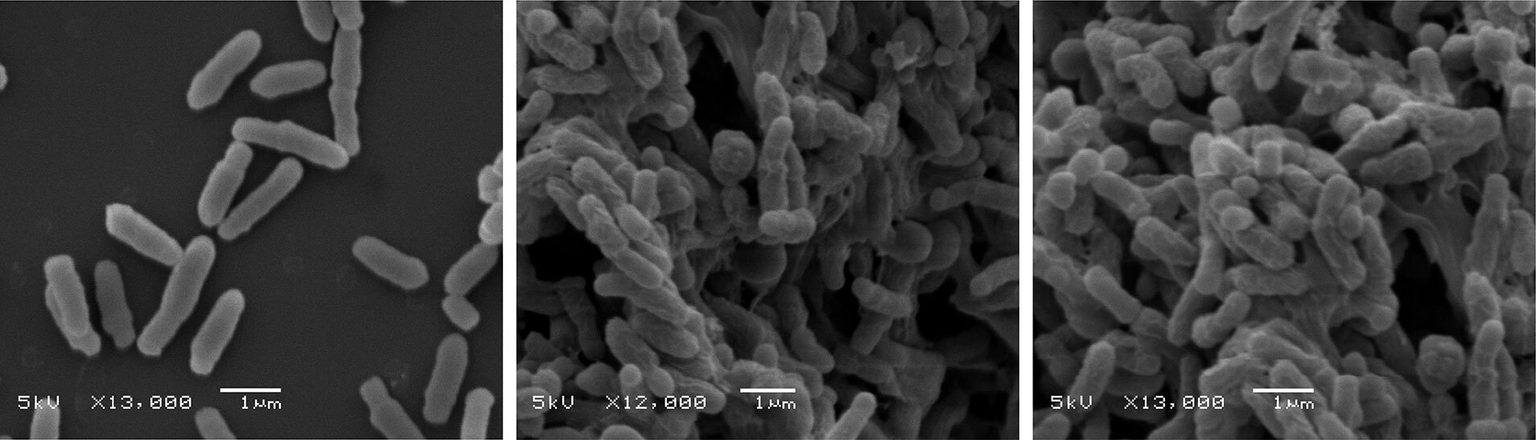

Scanning electron microscopy images showing bacterial membrane damage when treated with high doses of natural (middle) and synthetic (right) peptides compared to untreated bacteria (left).

By Rachel Scanza, Ph.D.

The advent of antibiotics more than a century ago brought huge benefits for human health. Previously lethal infections became manageable, making antibiotic drugs a cornerstone of modern medicine. Yet widespread use of antibiotics, combined with bacteria’s ability to rapidly evolve, has led to rising rates of antibiotic resistance in the body. In response, scientists at the Stowers Institute are turning to natural molecules in the immune systems nearly all organisms, including humans. These small proteins, known as antimicrobial peptides, can destroy a broad range of pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

“As antibiotic resistance rises, these proteins are actively being studied as alternatives in clinical trials,” said Stowers Institute Assistant Investigator Siva Sankari, Ph.D. “That makes it extremely important to understand how and where the peptides act inside bacteria.”

New research from the Sankari Lab sought to untangle how antimicrobial peptides function both as microbial weapons and finely tuned regulators of biological processes. The study, published in PLoS Genetics on December 18, 2025, reveals both how and where one well-studied peptide made by alfalfa acts on its bacterial partner.

In addition to their therapeutic promise, antimicrobial peptides also play critical roles in nature. Some plants, for example, use them not to kill microbes — but rather to control soil bacteria in a mutually beneficial partnership called symbiosis. In legumes such as alfalfa, bacteria obtain nitrogen from air and convert it into a biologically available form needed for plant growth. These peptides make this process more efficient by taking control over the bacteria.

Siva Sankari discussing research in the lab.

“Antimicrobial peptides don’t just kill bacteria — at low doses, they can reprogram them,” said Sankari. “This work gives researchers a roadmap for figuring out precisely how these peptides work.”

A lock-and-key approach

Symbiotic relationships are essential throughout biology. In the human gut, for instance, microbes aid digestion and nutrient absorption. The Sankari Lab focuses on a simpler and more experimentally accessible system: the symbiosis between plants and soil bacteria, which offers insights relevant to both agriculture and medicine.

Building on years of research on a plant peptide called NCR247 and its bacterial partner Sinorhizobium meliloti, the team aimed to tease apart how the peptide works. They wanted to distinguish its precise effects — when it binds to specific proteins inside the bacteria — from its broader, more general antimicrobial damage to the cell. To do this, they compared the natural “L-form” of NCR247 with a synthetic “D-form,” a mirror-image version of the peptide that cannot easily bind to bacterial proteins.

“All biological proteins are designed to fit only one way,” said Sankari. “If you use the mirror image, it won’t fit the lock-and-key interaction. It’s like trying to fit your right hand into a left-handed glove. That allowed us to determine whether the peptide’s effects come from specific protein binding or from more general physical interactions.”

Sankari further explained that mirror-image peptides are often used clinically because they are harder for cells to break down and are thus more stable. However, only few labs have used them to understand how peptides work inside cells, making this approach both novel and powerful.

At high concentrations, the researchers found that both peptide forms simply disrupt bacterial membranes, killing the cells. At lower concentrations, however, only the natural form activated the communication pathways required to form a healthy relationship with the plant.

An unexpected twist on transport

To understand where these effects occur inside bacteria, the team examined a mutant strain of S. meliloti lacking a crucial protein. Many bacteria have two membranes, and BacA, which resides on the inner membrane, is a transport protein known to import host peptides to the innermost part of the cell. Because BacA can shuttle both natural and synthetic forms, it offered a unique way to separate where the peptide is inside the cell from what its specific function is.

Assistant Investigator Siva Sankari, Ph.D.

“Our original goal was not to study BacA at all,” said Sankari. “We only realized its role when both the natural and synthetic peptides produced completely different responses in the BacA mutant.”

BacA had long been thought to protect bacteria from peptide-induced death, but how it did so, especially at very low peptide concentrations, remained unclear.

“We discovered the mechanism,” said Sankari. “BacA acts like a tap. It controls how much peptide stays in the outer compartment and how much enters the inner layer, preventing dangerous overstimulation while keeping the cell alive.”

By pulling peptides away from the cell’s outer layer and into the interior, BacA prevents lethal accumulation and signaling while allowing peptides to carry out essential intracellular functions — a balance required for successful symbiosis.

Understanding this balance, Sankari explained, has implications far beyond plants.

“With antibiotics, we discovered them, put them into the clinic, and only later faced widespread resistance,” she said. “To avoid repeating that problem with antimicrobial peptides, we need to understand exactly how they work before we rely on them.”

Additional authors include Markus Arnold, Ph.D., Vignesh Babu, Ph.D., Michael Deutsch, and Graham Walker, Ph.D.

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (award: R01GM031010) and by institutional support from the Stowers Institute for Medical Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

In The News

07 January 2026

From the Journal of Cell Science, Investigator Kamena Kostova named a 'Cell Scientist to Watch'

Read Article

#Stowers25: Celebrating 25 Years

06 January 2026

Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, Ph.D., reflects on a year of discovery, gratitude, and the community that helps support our mission.

Read Article

In The News

01 January 2026

From Science Friday, President and CSO Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado talks about the science of regeneration and the biology lessons we can carry into the new year.

Read Article