In The News

07 January 2026

Investigator Kamena Kostova, named ‘Cell Scientist to Watch’

From the Journal of Cell Science, Investigator Kamena Kostova named a 'Cell Scientist to Watch'

Read Article

News

Stowers scientists discover how metabolically specialized support cells orchestrate whole-body regeneration, reshaping our understanding of tissue repair and regenerative medicine.

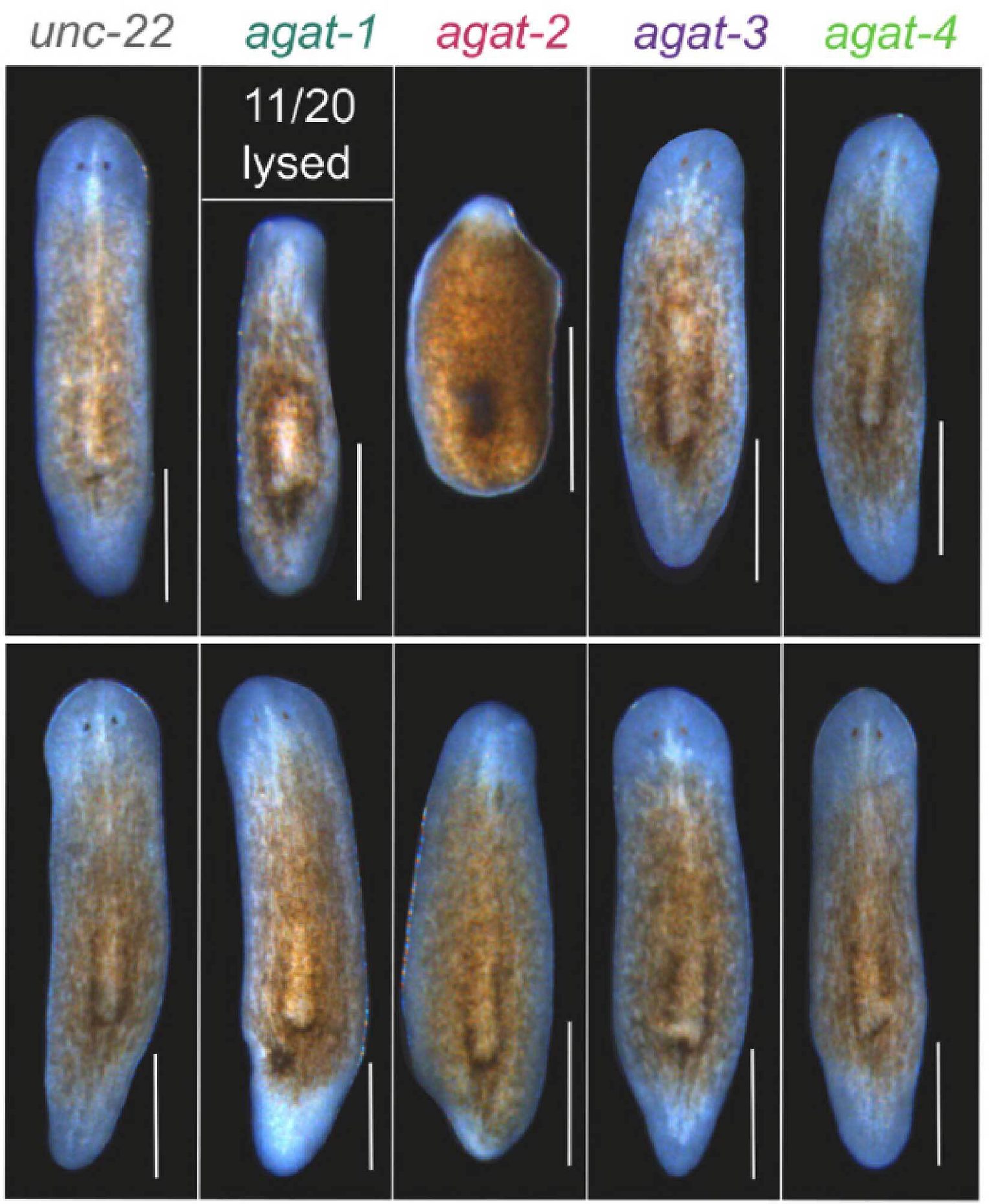

Microscopy images illustrating planarian flatworm regeneration at 14 days following amputation of the head and tail. Top panel shows RNA interference of agat+ cells while bottom panel illustrates regeneration rescue of agat+ with the metabolite creatine.

The planarian flatworm is a tiny freshwater organism famed for its extraordinary ability to regrow entire body parts from small fragments, a feat that has captivated scientists for over a century. For decades, researchers attributed this remarkable regenerative capacity almost exclusively to the worm's abundant stem cells, called neoblasts, which divide and differentiate to produce new tissue. Now, a recent study from the lab of Stowers Institute President and Chief Scientific Officer Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, Ph.D., reveals a radically different picture: regeneration is not the province of stem cells alone, but rather depends on the coordinated activity of specialized support cells that metabolically fuel the regenerative process.

Published in Developmental Biology, the study, led by former graduate student Aubrey M. Kent, Ph.D., reveals that a group of epidermal progenitor cells, called agat+ cells, do far more than simply mature into skin. Instead, these cells are metabolically active factories that produce and secrete key chemical substances, or metabolites, that power planarian stem cells and enable successful tissue regeneration.

"Planarians have long fascinated us because they can regrow an entire body from a tiny fragment, but we have mostly focused on the stem cells that rebuild the animal," said Sánchez Alvarado. "What this work shows is that regeneration does not belong to stem cells alone, but that differentiated support cells and their metabolism are just as critical to making regeneration possible."

For nearly two decades, agat+ cells (named after the enzyme they express, arginine:glycine amidinotransferase, or AGAT for short) were considered little more than a transient way station in the journey from stem cell to mature skin. The study systematically characterized all five members of the planarian agat gene family and revealed that four of them (agat-1, agat-2, agat-3, and agat-4) are co-expressed in specialized populations of epidermal progenitors, which accumulate at wound sites following injury. The fifth gene, agat-5, is barely expressed and is dispensable for regeneration.

By performing targeted knockdowns, the researchers uncovered functionally distinct roles for these genes. agat-1 proved essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis under normal conditions, while agat-2 emerged as indispensable for blastema formation—the early outgrowth of cells required for regeneration—and for sustaining the proliferation and overall maintenance of the stem cell pool during regeneration.

"For nearly two decades, agat+ cells were considered little more than waypoints on the road to a mature epidermis," said Sánchez Alvarado. "Our study reveals that they are, in fact, metabolically specialized support cells that help orchestrate regeneration across the whole animal."

Using advanced cell sorting and RNA sequencing, the team isolated agat+ cells and profiled their complete set of expressed genes. The results were striking: agat+ cells are enriched for RNA transcripts coding for proteins involved in metabolic pathways, particularly creatine and ornithine synthesis, and packed with as well as others encoding transport proteins and secretion machinery. These cells produce the molecular machinery needed not just to synthesize metabolites, but actively to export them for use by neighboring tissues.

"By uncovering that agat+ cells are wired to produce and export metabolites like creatine and ornithine, we are beginning to see regeneration as a profoundly metabolic problem," said Sánchez Alvarado. "Injury does not just trigger cell division; it demands a coordinated redistribution of energy and metabolites to the tissues that need them most."

Critically, the researchers demonstrated that these planarian AGAT proteins retain a highly conserved active site when compared to their human counterparts, indicating that they remain enzymatically competent and capable of producing these essential metabolites.

To test whether metabolites produced by agat+ cells are truly required for successful regeneration, the team knocked down AGAT genes and then attempted to rescue the regenerative defects by supplementing the worms with creatine—one of the main products of AGAT enzymatic activity and a critical energy buffer in cells. The results were unambiguous: creatine supplementation partially rescued the regeneration defects observed after agat-2 knockdown, allowing worms to form larger anterior and posterior outgrowths.

"The fact that creatine supplementation can partially rescue the loss of agat-2 tells us that specific metabolic pathways are not merely correlative. They are functionally required for successful regeneration," said Sánchez Alvarado. "That is a powerful conceptual shift, because it suggests we might one day tune regenerative capacity by tuning metabolism."

Yet the rescue was not complete: creatine supplementation did not fully restore survival or tissue homeostasis in AGAT knockdown animals, suggesting that other metabolites such as ornithine, homoarginine, or as-yet unidentified molecules, also contribute to regenerative success. This partial rescue points to a richer, more complex metabolic landscape underlying tissue repair.

Together, the findings redefine agat+ cells as a previously unappreciated cellular compartment, not a transient progenitor state destined for oblivion, but rather a stable, heterogeneous population of post-mitotic support cells embedded beneath the epidermis, dynamically adjusting their metabolic output in response to injury.

"Our data argue that agat+ cells behave like a dispersed endocrine organ embedded just beneath the skin," said Sánchez Alvarado. "They do not divide, and they cannot change their fate, yet they dynamically adjust what they secrete in response to normal tissue turnover and injury to sustain stem cells and rebuilding tissues. This is 'flexibility without plasticity,' and it adds a new dimension to how we think about the cellular players in regeneration."

“What makes this discovery especially exciting is that it challenges previous assumptions about how regeneration works,” Kent said. “It allows scientists in our field to rethink how animals rebuild themselves.”

The broader significance of this work extends well beyond planarian biology. Many vertebrate tissues, including the gut epithelium, bone marrow, and skin, harbor populations of transient progenitors and differentiated supporting cells that are incompletely understood. If these cells function similarly to planarian agat+ cells, supplying metabolic support to their associated stem cells, the same principles might apply across the animal kingdom.

"Although this work is rooted in a flatworm, the principles it uncovers are not," said Sánchez Alvarado. "Many vertebrate tissues harbor transient progenitors that might similarly provide metabolic support to stem cells. Understanding how planarian agat+ cells fuel regeneration could ultimately help us design strategies to boost repair in less regenerative animals, including humans."

The study opens new avenues for regenerative medicine: by identifying which metabolic support cells exist in a given tissue and determining how to enhance their function, researchers might one day accelerate wound healing, facilitate organ repair, or even unlock latent regenerative capacity in tissues that have lost it.

"Our findings suggest that supporting cells with the right metabolism could be as critical as stem cells themselves," said Sánchez Alvarado. "This could, some day in the future, translate to new therapies that may help us recover from injury."

Acknowledgements: The research was conducted in close collaboration with the Stowers Institute Technology Center, whose expertise in cell sorting, RNA sequencing, and genomic analysis was essential to the study's success. The work demonstrates the power of integrating classical developmental biology approaches with modern molecular and computational tools to reveal new dimensions of how tissues repair and renew themselves.

Citation: Kent, A.M., Guerrero-Hernández, C., Brewster, C., McKinney, S., Morrison, J.A., McKinney, M.C., Ross, E.J., Mann, F.G., Benham-Pyle, B.W., & Sánchez Alvarado, A. (2025). Metabolites produced by agat+ cells support regeneration in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Developmental Biology, 529, 106–120.

About the Stowers Institute for Medical Research

The Stowers Institute for Medical Research is a nonprofit, foundational biomedical research organization dedicated to improving human health by studying the fundamental processes of life. Founded in 1994 through the generosity of Jim Stowers, founder of American Century Investments, and his wife, Virginia, the Institute opened its research facility in Kansas City, Missouri, in 2000. Today, the Institute is home to roughly 500 members, including more than 20 independent research programs and numerous technology development and core facilities, all focused on understanding the secrets of life and advancing innovative approaches to the causes, treatment, and prevention of disease.

Additional authors include Carlos Guerrero-Hernández, Carolyn Brewster, Sean McKinney, Ph.D., Jason Morrison, Mary McKinney, Ph.D., Eric Ross, Frederick Mann, Ph.D., and Blair Benham-Pyle, Ph.D.

This work was funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (award: R37GM057260), support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and with institutional support from the Stowers Institute for Medical Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

In The News

07 January 2026

From the Journal of Cell Science, Investigator Kamena Kostova named a 'Cell Scientist to Watch'

Read Article

#Stowers25: Celebrating 25 Years

06 January 2026

Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, Ph.D., reflects on a year of discovery, gratitude, and the community that helps support our mission.

Read Article

In The News

01 January 2026

From Science Friday, President and CSO Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado talks about the science of regeneration and the biology lessons we can carry into the new year.

Read Article